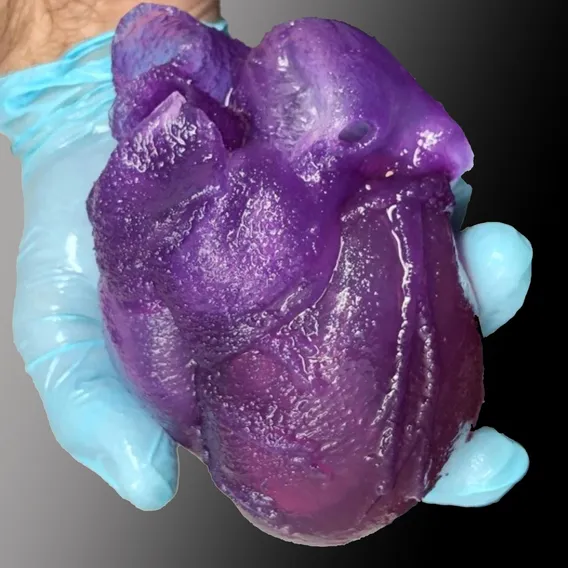

WEB DESK, July 3(ABC): Professor of Biomedical Engineering Adam Feinberg and his team have created the first full-size 3D bioprinted human heart model using their Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels (FRESH) technique. Showcased in a recent video (below) by American Chemical Society and created from MRI data using a specially built 3D printer, the model mimics the elasticity of cardiac tissue and sutures realistically. This milestone represents the culmination of two years of research, holding both immediate promise for surgeons and clinicians, as well as long term implications for the future of bioengineered organ research.

The FRESH technique of 3D bioprinting was invented in Feinberg’s lab to fill an unfilled demand for 3D printed soft polymers, which lack the rigidity to stand unsupported as in a normal print. FRESH 3D printing uses a needle to inject bioink into a bath of soft hydrogel, which supports the object as it prints. Once finished, a simple application of heat causes the hydrogel to melt away, leaving only the 3D bioprinted object.

While Feinberg’s lab has proven both the versatility and the fidelity of the FRESH technique, the major obstacle to achieving this milestone was printing a human heart at full scale. This necessitated the building of a new 3D printer custom made to hold a gel support bath large enough to print at the desired size, as well as minor software changes to maintain the speed and fidelity of the print.

Major hospitals often have facilities for 3D printing models of a patient’s body to help surgeons educate patients and plan for the actual procedure, however these tissues and organs can only be modeled in hard plastic or rubber. Feinberg’s team’s heart is made from a soft natural polymer called alginate, giving it properties similar to real cardiac tissue. For surgeons, this enables the creation of models that can cut, suture, and be manipulated in ways similar to a real heart. Feinberg’s immediate goal is to begin working with surgeons and clinicians to fine tune their technique and ensure it’s ready for the hospital setting.

“We can now build a model that not only allows for visual planning, but allows for physical practice,” says Feinberg. “The surgeon can manipulate it and have it actually respond like real tissue, so that when they get into the operating site they’ve got an additional layer of realistic practice in that setting.”