ISLAMABAD, July 15 (ABC): It may be a surprising fact that many older men lose the Y chromosome in their white blood cells when they hit a certain age.

Now, new research finds that this genetic change can cause serious heart problems and increase the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Known as mLOY, or mosaic Loss Of YTrusted Source, this genetic change affects at least 20 percent of 60-year-old men and 40 percent of 70-year-old men, according to researchers at the University of Virginia and Uppsala University in Sweden.

“The Y is lost during cell division and is more common in tissues and organs with high cell division rates, such as the blood,” Lars Forsberg, Ph.D., a study co-author and an associate professor at the Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology at Uppsala University, told Healthline. “Replicated risk factors are age, smoking, and genetic predisposition.”

The new study, led by Forsberg and Kenneth Walsh, Ph.D., a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, establishes a causal link between chromosome loss and the development of fibrosis in the heart, impaired heart function, and death from cardiovascular diseases in men.

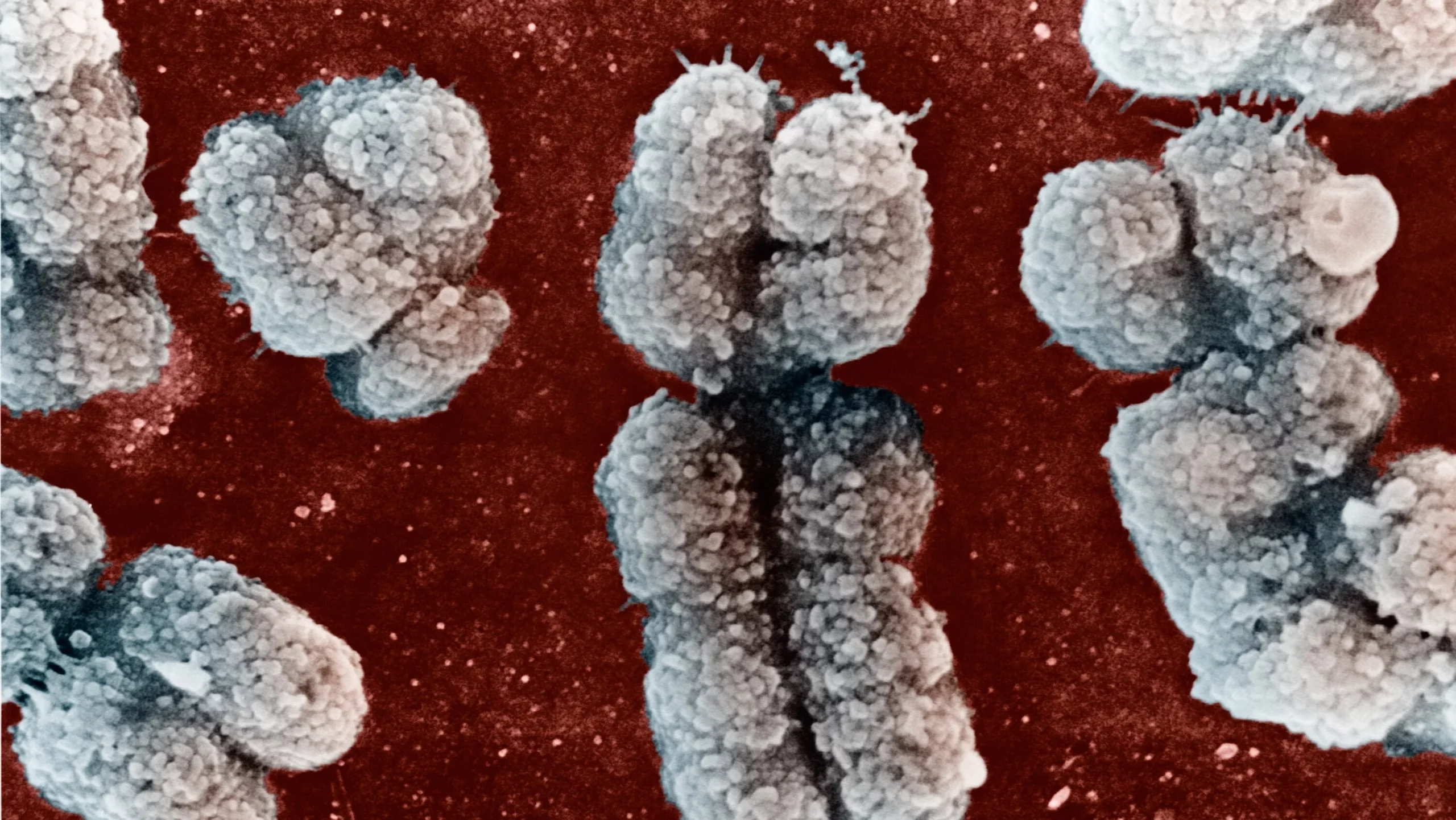

Researchers used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to remove the Y chromosome from white blood cells in lab mice. They found that mLOY caused direct damage to the animals’ internal organs and that mice with mLOY died younger than mice without mLOY.

“Examination of mice with mLOY showed an increased scarring of the heart, known as fibrosis. We see that mLOY causes the fibrosis which leads to a decline in heart function,” said Forsberg.

How the process works

The researchers reported that mLOY in a certain type of white blood cell in the heart muscle, called cardiac macrophages, stimulated a known signaling pathway that leads to increased fibrosis.

When the researchers blocked this pathway, known as heart trigger high transforming growth factor ß1 (TGF-ß1), they said the pathological changes in the heart caused by mLOY could be reversed.

An epidemiological study in humans also showed that mLOY is a significant risk factor for death from cardiovascular disease in men.

For that portion of the study, Forsberg, Walsh and colleagues looked at genetic and cardiovascular data on 500,000 individuals ages 40 to 70 in the UK Biobank.

The researchers reported that individuals with mLOY at the start of the study had about a 30% higher risk of dying from heart disease during the 11-year follow-up period than those who did not have mLOY.

“This observation is in line with the results from the mouse model and suggests that mLOY has a direct physiological effect also in humans,” said Forsberg.

Preventive measures

Forsberg said routine testing for the loss of the Y chromosome in blood cells could help prevent cardiovascular disease.

“mLOY testing of aging males would identify the… men [who] would likely benefit from medical checkups and preventive treatments,” Forsberg said. “Loss of the Y chromosome can be relatively easy to measure. If validated by further research, the loss of Y can be used as a prognostic assay or it potentially can be used to guide therapies.”

“For example, men with mLOY in blood could be directed to undergo an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) analysis to determine whether he has a buildup of connective tissue/fibrosis in his heart and other organs,” he said. “If that is found to be the case, he could be put on anti-fibrosis medications.”

“An FDA-approved antifibrosis medication exists for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and this drug is currently being explored for its utility in conditions that involve cardiac and kidney fibrosis,” Forsberg added. “In addition, there is a lot of interest in developing new fibrosis medications by pharmaceutical companies. It is possible that men with loss of the Y chromosome would have a superior response to these medications.”